Yellowstone: Where the Bison Roam

Where the Bison Roam - Yellowstone National Park

The bald eagle may be the USA’s national emblem, but there’s arguably no more singularly North American breed than the bison. In fact, it was named America’s national mammal in 2016.

Brought back from the brink of extinction, it’s also a shining symbol of resilience.

And there’s no better place in which to view these wild, majestic creatures than in Yellowstone National Park. The bison population fluctuates from 3,000 – 6,000 animals within its borders. The northern herd breeds in the Lamar Valley and on the high plateaus around it. The central herd breeds in Hayden Valley. In the past decade or so, their numbers have exploded, notes Virginia Miller, lead instructor at the nonprofit Yellowstone Forever, the official non-profit partner of Yellowstone National Park. There are more free-roaming bison in the park than anywhere else in the country.

Historically, huge herds of these lumbering behemoths — the largest land mammal in North America — roamed an area from northern Canada to northern Mexico. By the 1800s, they were still prolific in the western United States. But mass poaching later in the century decimated their numbers. In 1887, when chief Smithsonian taxidermist William Hornaday made a trip west, he was shocked at what he didn’t see: namely large numbers of bison. Herds that once numbered in the millions had dwindled to the hundreds, thanks to a host of reasons, including poachers, sport hunters, farmers and ranchers, drought, and more efficient killing methods, such as the use of guns and horses.

One such poacher, the notorious Ed Howell, declared in 1884 that “he was going to kill every last bison in Yellowstone” and operated with impunity, Miller recounts. There were rules against slaughtering animals in America’s first national park, but no real repercussions for those who did. The decapitated heads of the animals were hung from trees to dry and sold to taxidermists who marketed them as trophies for up to $300 each (about $8,000 today), Miller says.

That changed in 1894 when the Lacey Act, named for an Iowa congressman who sponsored the legislation, gave park personnel the authority to arrest lawbreakers.

For his part, the Smithsonian’s Hornaday, who became the institution’s first Department of Living Animals chief, brought 15 bison to display on Washington, D.C.’s National Mall. In 1891, they were among the first residents of the newly established National Zoo.

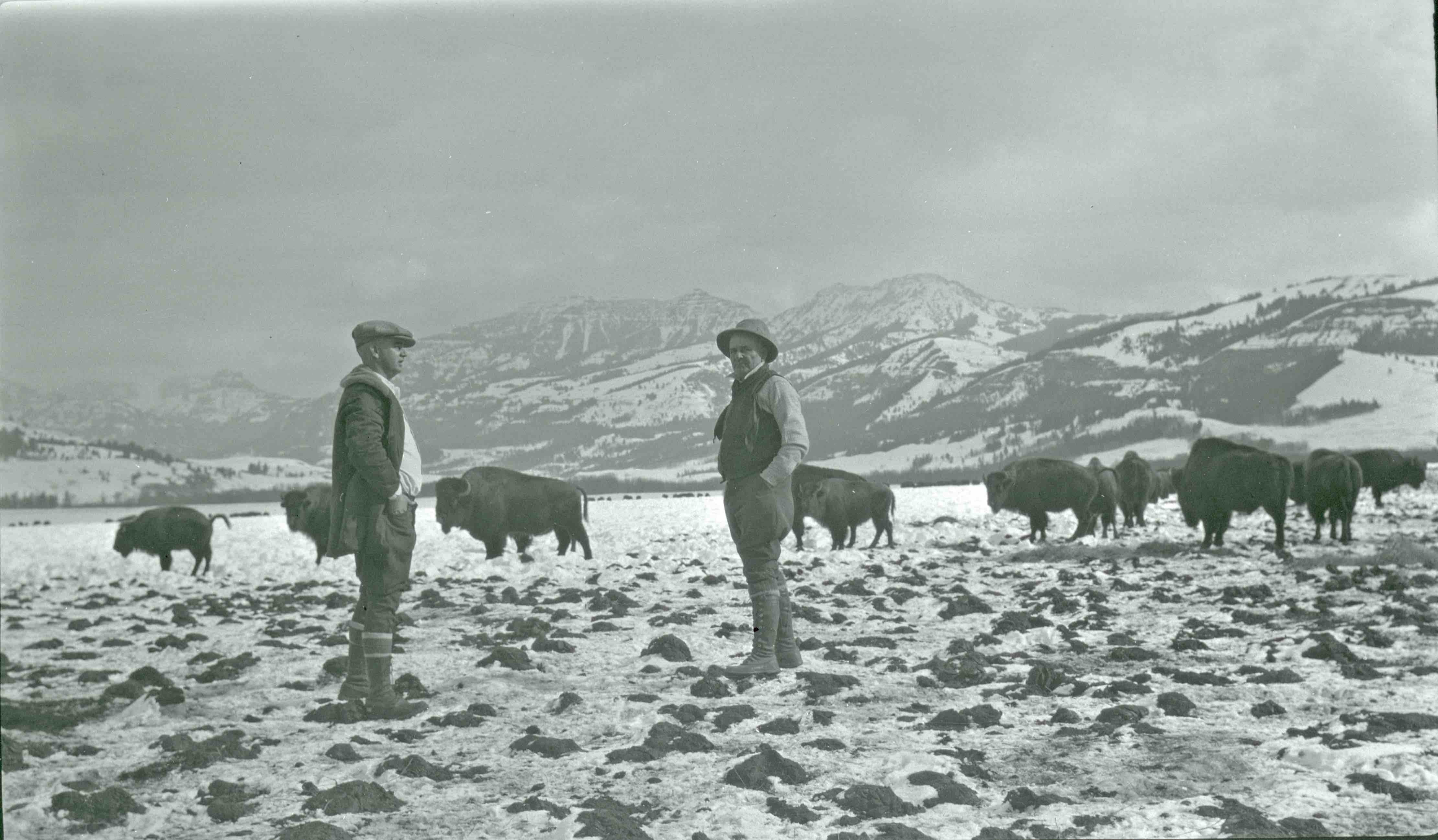

But new laws like Lacey’s and fledgling conservation programs like Hornaday’s did little to boost Yellowstone’s bison population. Officials counted a scant 25 of the animals in 1901. That year, Congress approved funding to boost the ranks by buying 21 bison from private owners. By 1907, they were housed at the park’s Lamar Buffalo Ranch — which still exists as an educational facility — and eventually released into the park.

These days, Yellowstone visitors are almost certain to spot a bison — or, more likely, dozens. But keep your distance.

As Miller puts it, “They’re pretty chill — until they’re not.” The National Park Service requires staying at least 25 yards away from bison. Not only are they unpredictable, they can sprint up to three times faster than you can. Still, they’re an undeniable thrill to see roaming free in their habitat.

For a safe and illuminating look at bison and other wild park inhabitants, consider joining one of the many park tours. Staying in the park is the best way for visitors to experience all it has to offer, including the exciting wildlife watching.

Washington, DC-based freelance writer Jayne Clark has been a travel reporter at USA TODAY and several other daily newspapers. First published Aug 2, 2018.

For A World of Unforgettable Experiences® available from Xanterra Travel Collection® and our sister companies, visit xanterra.com.

Want to experience Yellowstone in-depth? See what makes Yellowstone National Park a great place to work for a season or longer!